Traumatic Vertebral Artery Dissection in Children

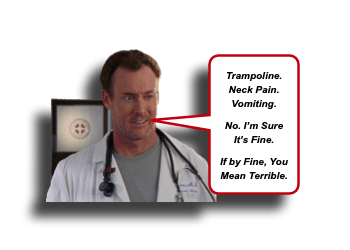

Oh, trampolines how I despise you. No, I am not a killjoy. Yes, I am a hypocrite (as I once enjoyed flinging myself through the air as I tried to test my immature abilities to avoid other human flying objects sprung upward from the trampoline surface). It is merely a learned response derived from caring from so many children who have had broken limbs, skulls, and neck injuries associated with trampolines. Recently, we discussed how an isolated seatbelt sign on the neck should not be equated to cervical vascular injury. Sure the forces a child experiences during a car accident can be profound, but the seatbelt more often than not is a good protector. Unfortunately, trampolines have no useful protective devices. Let’s take a minute to review one potential critical injury that may be missed upon first evaluation – Traumatic Vertebral Artery Dissection in Children:

Traumatic Vertebral Artery Dissection in Children: Basics

Rare, but potentially devastating

- Vertebral Artery Dissection (VAD) is difficult to diagnose and often is missed on first presentation. [Mortazavi, 2011]

- Compared to Carotid Artery Dissection, VAD is more often associated with ischemic stroke. [Kumar, 2018]

- Dissection of the cranio-cervical arteries accounts for 20-25% of ischemic strokes in young adults. [Pandey, 2015]

- While VAD may occur spontaneously, traumatic causes account for the majority (81%) of cases. [Pandey, 2015]

Anatomy matter

- The vertebral artery is relatively immobile. [Kumar, 2018]

- It is anchored within the bony cervical spine (especially from C2-C6).

- It wraps around bony prominences of C1-C2 before entering the foramen magnum.

Minor mechanism can lead to major problems

- Numerous cases of “minor” athletic injuries (ex, during wrestling) and closed head injuries that are associated with VAD. [Kumar, 2018]

- Spinal/Cervical manipulation is also been associated with VAD.

- Jumping on “bounce houses” and Trampolines [Ripa, 2017; Casserly, 2015]

When treated promptly, outcomes are good. [Pandey, 2015; Mortazavi, 2011]

- The best management strategy for children with VAD is still debated.

- Most patient receive anti-platelet medications.

- Some will receive anticoagulation.

- Vascular stenting has also been utilitied.

Traumatic Vertebral Artery Dissection in Children: Presentation

Head and/or Neck Injury with “posterior circulation ischemia symptoms” require consideration of Vertebral Artery Dissection.

- Persistent dizziness

- Vomiting

- Cerebellar ataxia

- Gait ataxia

- Limb ataxia

- Dysarthria

- Nystagmus

- Unilateral limb weakness can also be seen.

- Some even report transient neurologic deficits.

Physical exam to help differentiate from “concussion” symptoms:

- Certainly, the symptoms of headache and dizziness and vomiting may mimic those of concussion syndrome.

- Since the incidence of concussion is much greater than VAD, be more specific in the cerebellar assessment: [Kumar, 2018]

- Look for limb ataxia (ex, Finger to Nose and Heel to Shin)

- Look for focal weakness

- Look for presence of Babinski sign

- Look for nystagmus (ex, “eye ataxia”)

- Look for visual field cuts

- Look for bulbar weakness (ex, difficulty swallowing, nasal speech pattern)

- Look for gait ataxia (yes, get them up and walk them)

Moral of the Morsel

- Trampolines are not meant for children. ‘Nuff said.

- Dizzy and vomiting after blunt impact to the neck? Think Vertebral Artery Dissection.

- “Non-focal Neuro Exam” is not an exam at all. Since VAD is rare, we can’t irradiate everyone, but we also cannot just document “moves all extremities equally” to adequately assess for possible VAD. Be more thorough.

- Ataxia applies to more than walking. Check eyes, speech, and limbs!